Colour Farming on Cape Breton Island - Year 1

Those who follow Mamie’s Schoolhouse on Facebook and Instagram know that I have been working on commercial scale dye plant farming on Cape Breton Island for some time, and am now in collaboration with two farmers on the island with decades of experience in growing a broad range of crops without the use of any synthetic pesticides, herbicides, etc.

Both farmers are committed to ecological soil, water and crop management and, because their farms are in distant parts of the island, we’ll have an opportunity to compare results from different local micro-climates, soil conditions, etc.

This follows on from close to five years of small plot trials of many different dye plants on my own property.

Anthemis tinctoria / Dyer’s Chamomile grown at Mamie’s Schoolhouse.

Before making a final decision about which ones to grow for the 2019 commercial scale-up trials, I met with the provincial Department of Agriculture to ensure that they had no concerns with the short-list we were considering. I am committed to protection of our planet’s precious ecology, and spent a previous career in public policy management, so I very much value the input of the provincial experts who confirmed that none of the three species we are trialling are listed as problem plants in Nova Scotia.

Two of the species - Reseda luteola / Weld and Isatis tinctoria / Woad - are considered noxious weeds in several southern and western North American regions, so it pays to be cautious, particularly as the impacts of climate warming push the boundaries of many species ever further northward, and alter local ecosystems in ways that may make introduced species problematic that are now considered benign. The third species - Coreopsis tinctoria / Dyer’s Coreopsis - is native to much of the north-eastern part of Canada and the US, though not to Nova Scotia, but it is not invasive.

Dennis Laffan’s farm, North River Organics.

In early June, 2019 seeds were sown at both farms. This timing is a little later than sowing would generally take place. However, our Spring in this part of Canada was about three weeks later than normal, so really we were right on time!

Tiny Reseda luteola / Weld seeds mixed with agricultural lime.

For this first commercial-scale trial, we chose to grow only three types of dye plants, as we didn’t want to be overly ambitious and stretch ourselves too thin. We were confident that there would be many lessons learned that will stand us in good stead when we move on to an expanded range of dye plants in subsequent years.

Michelle Smith’s farm, North Wind Farm.

Two of the trial species - Reseda luteola / Weld and Isatis tinctoria / Woad - are biennial, meaning they flower/produce seed in the second year. Both are reputed to produce the best pigment in the first year rosette leaves, but Weld’s second year flowers are the most in-demand part of that plant.

Our Experience

It was an awful year for farming.

A very late, very cold Spring, a cold Summer, torrential downpours, Hurricane Dorian, then some very cold weather far earlier than usual in Autumn, meant that every type of farmer in the province faced multiple challenges this year.

Sky Glen Valley, where Michelle’s farm is located, was hammered by Hurricane Dorian in early September.

Our experience was that, for one of the farmer’s, absolutely nothing grew. But rather than just blame the unforgiving growing conditions this year, we think it also had to do with two mistakes on our part - direct sowing, which meant that aggressive, fast-growing weeds were able to crowd out the dye plants before they had a chance to put on any growth themselves, and soil that was far too rich for them (most dye plants prefer poor, rocky soil).

The other farm fared much better. We were only growing two of our three trial plants there - Woad and Dyer’s Coreopsis - and got a decent crop from both. The soil on that farm was much less cultivated than on the farm where nothing grew.

In early August, it was so exciting when the first plants started to put on some growth. This is a row of Dyer’s Coreopsis.

I was able to identify the Woad for the farmer. It looks a lot like some pretty invasive weeds we have here, so were both pretty excited when we found a good, strong row of Woad growing.

Dyer’s Coreopsis was harvested throughout the late Summer and early Autumn. The more the flowers are picked, the more flowers the plant produces (this is standard with flowering plants), so the farmer collected flowers every time there was work to do in the surrounding vegetable rows. The plants were finally spent in early October after a couple of successive frosty nights.

The first decent Woad harvest was gathered in mid-September.

I had more than enough of both plants for the ‘first harvest’ workshop I had scheduled to teach at the Inverness County Centre for the Arts during our island’s annual Celtic Colours International Festival in mid-October, and enough to also do some tests with our Woad using the salt rub method with fresh leaves (as opposed to the more traditional pigment extraction, fermentation, and vat reduction methods). I took pains to properly rinse the leaves before use, as advised by Ian Howard who used to run The Woad Centre in Norfolk, England, prior to his retirement, and who has been an enormous help and source of expert advice to me during this trial process. Growing so close to the ground, Woad rosette leaves tend to be covered in soil, which can impact on dye results if not washed off first.

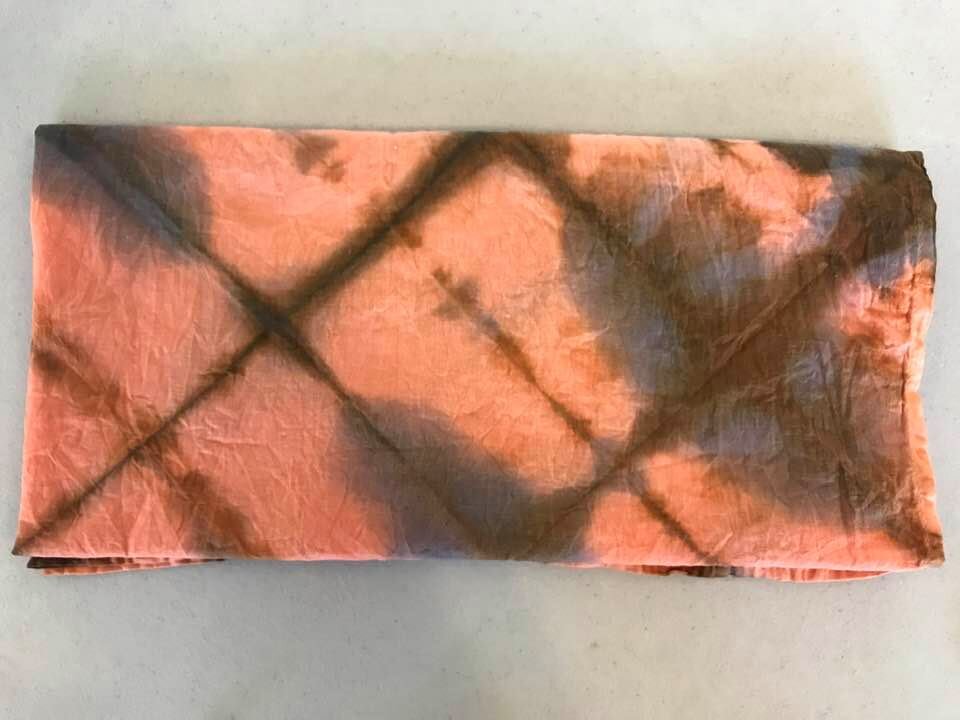

I was really thrilled with the gorgeous results, especially as the above were the very first textiles dyed with Cape Breton Island grown Woad (in modern times, anyway; it’s entirely likely that some Gael settlers on this island would have brought Woad seed with them, though any memory of that has been lost). It felt like such an honour to be holding the cloth in my hands, having seen the colour through from idea to planning, and from seed to dye, and having seen the hard work invested by my farmer collaborators.

With most of the Woad, I did a water extraction and created dry, powdered material. This was a big learning curve for me, as I’d never gone through this entire process with Woad before, and I have a long list of things I’ll do differently next time! The biggest lesson learned was the enormous ratio between fresh plant material and final, dried pigment - by weight, it was approximately 200:1! I also accidentally deleted all of my photos from this process, and didn’t realize it until it was late to take some replacement ones of even the end stage.

Cape Breton grown and processed Woad in a reduction vat.

For the first harvest celebratory workshop that I taught in mid-October, I talked about the work that my farmer collaborators and I had done for this first commercial scale trial, the history of these dye plants, and our hopes for the future in terms of sustainably diversifying the economy of our beautiful island through colour farming. I taught the students how to make a reduction vat with Cape Breton Island grown Woad, dye baths with the Dyer’s Coreopsis, as well as with Madder (Rubia tinctorum) that I have been growing on my own property for several years, and how to use resist techniques to lay down different layers of colour on the cloth.

It was a wonderful day, in a gorgeous ocean-side setting, with a fabulous group of natural colour enthusiasts, and a very fitting way to celebrate the results of Cape Breton Island’s first year commercial dye plant farming trials.

Next Steps

My farmer collaborators and I are meeting soon to plan for next year. We’ll go through all of the many lessons learned from this first trial, and plan for greater success next year - the climate, weather, and dye plant Gods willing. Our aim is to try again with Weld (it’s so worth it), but also to expand the number of different dye plant species we grow, and to start most of them indoors in seedling flats in very early Spring.

We got one final flush of Woad leaves in early November (none of the ten or so frosts we’d had up until then had managed to fully kill it). I am currently drying those leaves. Drying Indigo or Woad leaves has traditionally not been considered advisable, due to a loss of the indigo precursor compounds in the leaf. However, early in November, natural dye master and biochemist Michel Garcia published the results of a new organic vat method for working with dried Indigo leaves that yielded beautiful, deep blues. He mentioned that he is going to do experiments with dried Woad leaves too, so I am saving my last harvest in the hopes that a method for working with them in a dried state is proven to be effective. Being able to dry leaves, and still get good dye results, would be enormously labour-saving over traditional methods, so fingers crossed.

In the meantime, I’ve decided to hold on to what I have left from our harvest. I’m working with a biochemist to conduct pigment quality control studies, and will use our remaining harvest to support this process. The aim is to take a lot of product to the market next year instead.

With thanks from Michelle, Dennis, and me (Mel) for coming along with us on our hopeful wee journey. See you in the colour-full farm fields next year!