Talking Orchil...

The Leeds Archive

Thirteen years ago, close friends living nearby decided they were going to up sticks and move house. I didn't realise at the time, but I was about to embark on rather a different journey. The friends asked me if I could look at some family papers being brought down from their attic because I knew something about natural dyes, and their forebears had been dye manufacturers in Leeds, Yorkshire. The papers related to a family business which started in the early years of the nineteenth century.

The basics of my research into the family papers (which I'll refer to as the Leeds Archive) are written up in my own blog which is the best place to read the core story of the company and the remarkable family that started it: there is a link at the end of this blog. I am still working on the papers that descended from the attic, and the reason I'm so keen to work on the recipes in the Stockholm and Leyden Papyri project is because the Leeds manufacturers started out in the successful manufacturing of orchil and cudbear.

What is orchil?

Orchil is a historical purple dye made from a wide variety of lichens whose use stretches back into pre-history. It was a staple dye for European dyers until the mid nineteenth century, although known to be highly fugitive. The unique beauty and freshness of its colour was greatly valued by dyers and analysis has confirmed its use in many costly textiles such as tapestries, and artefacts such as parchments. The dye is not available directly from the raw dyestuff and lichen must go through a lengthy fermentation, often of several weeks, to allow the dye precursors to develop into the characteristic purple.

The Orchil Trade

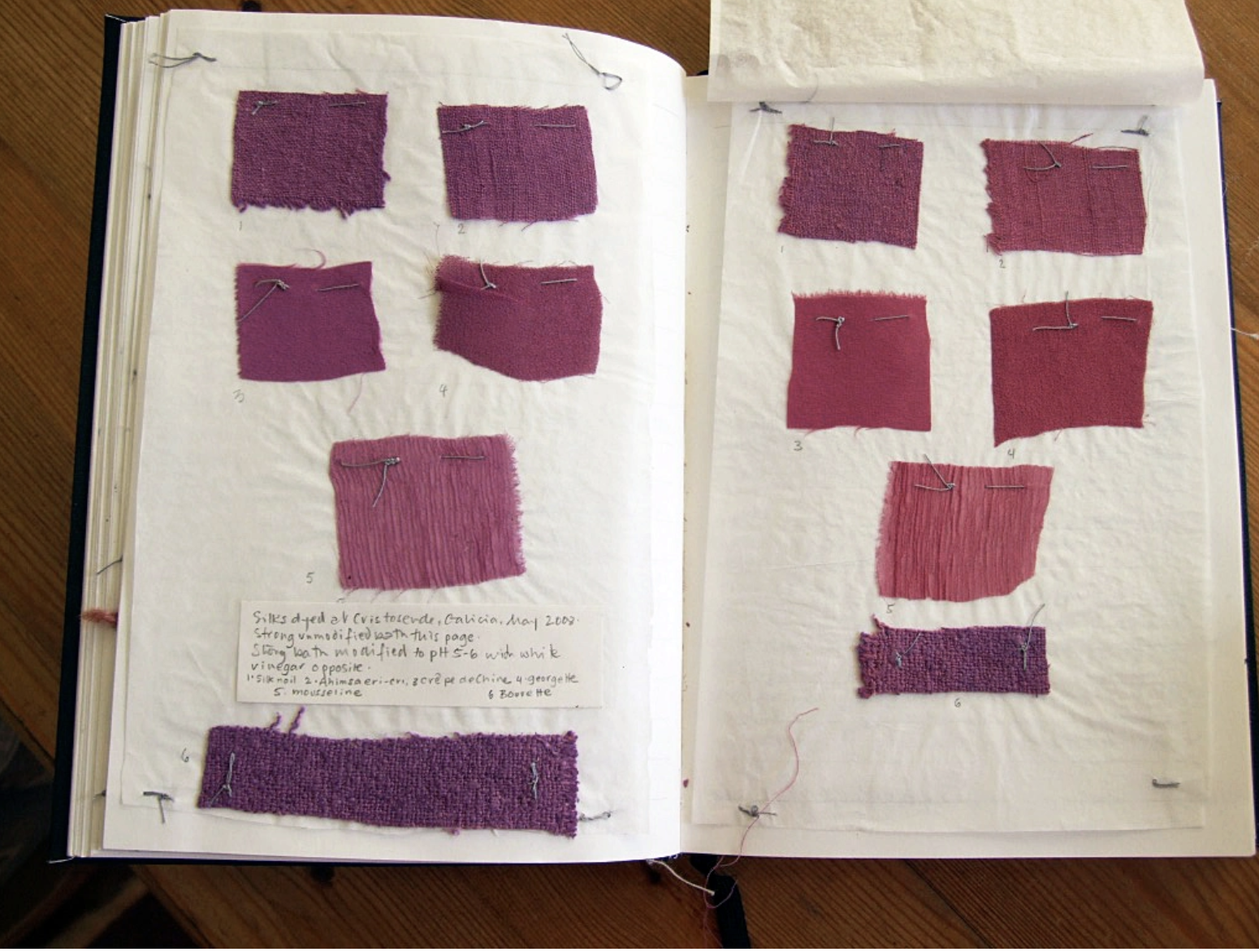

Samples dyed in 2008 after studying in Galicia. Samples on the right hand page were modified using white vinegar

My first research into orchil was to find out something of lichen sources throughout history, and which species were collected for the trade. I was so intrigued by the dye that I travelled to Galicia in Northern Spain to study orchil dyeing with weaver Anna Champeney, and later to Ecuador to follow up on a letter I'd found in the Leeds Archive. The relentless demand for orchil in the nineteenth century drove merchants further and further afield to find new sources, and the stories of West African and South American orchil lichens identified in the 1830s were documented in notes and a number of letters in the Leeds Archive.

Angola

In the case of lichen from Angola, an agent's letters from Lisbon reveal day-to-day issues affecting the buying and selling of orchil from the Portuguese colonies, and the secrecy in which deals were made in order to profit from a new source. They also record the story of Francisco Rodrigues Batalha, a Lisbon merchant. Batalha was a speculator and in 1837 co-opted a sea-captain named Ribeiro trading along the West African coast to search for new sources of dye lichens wherever he put into port. Batalha gave Ribeiro a 'reagent', which was likely to be ammonia. If orchil lichen is placed in ammonia and shaken regularly it will start to turn pink in around 24 hrs.

Through Batalha's enterprise Ribeiro located a likely lichen and a hitherto unknown and abundant source of dyestuff was discovered in Angola so that a new trade developed. 'Angola Weed', as it became known in Great Britain, was especially valued for its rich dye content. Batalha made - and apparently lost - a fortune dealing in the lucrative dyestuff.

Luanda was Angola’s main port and a slave capital until 1836, when Portugal abolished the transatlantic trade. Research suggests that human cargo was a part of Ribeiro's business but I haven't ascertained whether Batalha was also involved. Enslaved people, or enforced labour, were recorded in the Leeds letters as involved in carrying lichen to port from the interior until around 1858.

I wonder whether, with the abolition of the transatlantic trade in 1836, Batalha was prompted in 1837 to find a new commodity to keep ships' holds full?

Ecuador

A set of letters from the Leeds Archive also describes the search for orchil lichen in 1837 in the area of modern-day Ecuador. The accounts were written by a George W. Bruce, the son of a Scottish merchant located in Tenerife who dealt, among other things, in dyestuff. Bruce reported finding a new source of orchil lichen at Punta Santa Elena on the Ecuador coast, not far from Guayaquíl. Bruce's expedition thus identified another commercial source of orchil lichen and a trade to Europe followed. It is possible that Bruce took a collection of dye lichens with him to aid identification on a 'looks like' basis, or had studied such collections before embarking for South America. A collection of Canarian dye lichens (see image below) found in the Leeds Archive originated in Tenerife - and may have been compiled for this purpose.

I found a botanical collection of Canarian dye lichens in the Leeds Archive, dating from the 1830s and later identified as compiled by French botanist Jean-Marie Despréaux. This collection is now in the Economic Botany Collection, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

I have relatives in Ecuador and decided to make a trip to meet them and to follow up on Bruce's letter. In advance of the trip I was in touch with a mycologist on the Galápagos Islands who specialised in identification of lichens and he generously confirmed the modern name (Roccella gracilis) as the most likely lichen used in the dye trade. This enabled me to find images of it which I printed out and took with me. I wondered if there would be any left at Punta Santa Elena.

Using urine

On the outward flight I spied a dessert in a robust plastic container with a tight-fitting lid. In the interests of science I ate the dessert and I'll leave you to imagine the rest. I carefully transported a precious sample of my ageing urine down the spine of the Andes for several weeks until we reached Punta Santa Elena. The original area mentioned in Bruce's letter had become a restricted military base so I wasn't able to go in without risking arrest, and the Punta area was heavily built up. I felt that lichen was unlikely to be growing there any more.

My distant Ecuadorian cousins owned a beach house along the coast from Punta Santa Elena, a fact I hadn't known when I set out from England on my quest. From the serendipitously-located beach house I was able to explore the hot, arid and rather magnificent coast and hinterland by car, bus, and on foot. Eventually, I found a lichen closely resembling the images I had with me. It would not have been legal for me to take samples from the wild but I was able to take photographs in a few sites where I found what I believed to be Roccella gracilis.

I also found tiny windfall fragments and took some to immerse in the urine, which was by then ammoniac. The small samples turned the ammonia pink in just a few hours. I can still remember how excited I felt: that's probably why the photo below is so out of focus!

Roccella gracilis growing at Puerto LSmall fragments of R. gracilis steep[ed in stale urine and aerated for 12 hoursopez, Ecuador

Stockholm and Leyden Papyri

When I returned to the UK I continued to study orchil but never attempted to make it from stale urine, instead opting to use household ammonia (as opposed to ammonia at laboratory strength). Nineteenth century manufacturers knew that better results were obtained from purified ammonia and distilled their ammonia from stale urine but this option will not be open to me. For the project I intend to try to make four sets of orchil in parallel using two different orchil lichens. Two will be brewed up in stale urine and two in household ammonia.

How orchil should look when it's ready

Orchil can take a very long time to ferment and I have had several batches end in failure, with the dye sample remaining obdurately rust coloured. So although there appear to be endless weeks before our sample deadline, I need to leave myself time for it all to go horribly wrong. I hope to write a follow-up blog on my progress later in the project.

The Recipes: Stockholm 108 - 111

I have elected to study recipes Stockholm 108 -111. You can read the recipes by following the link at the end of the blog. It intrigues me that the recipes say nothing at all about how the orchil (archil) is made in the first place and simply advises how to use the orchil; it is assumed that the reader already has it to hand. There is a further oddity. In 110 the recipe states :

To dye in genuine bright red purple grind archil and take 5 cyathi of the juice for a mina of wool.

This is curious, because once orchil is made, it is in liquid form and one simply wouldn't grind it. And if you grind something, you don't then obtain a juice. If you grind lichen dyestuff and add water you will not produce a colour without the long fermentation.

Maybe the grinding refers to a form of dried orchil, similar to the cudbear of the Leeds Archive. Maybe it is a translation error, or maybe the original author didn't understand the process.

Using lichen today

I am often asked whether I recommend using lichens for dyeing. My least controversial reply is that I choose not to. Lichens are vulnerable organisms, highly sensitive to environmental change, and they cannot be cultivated. They are also hard to identify so that anyone without specialist knowledge often has little idea of what they are collecting. Is it a dye lichen? If so, is it endangered? If you can't identify it, how do you know?

Insofar as orchil is concerned it is very light fugitive and for studio work I prefer to use a more stable source for purple, such as an indigo / cochineal combination.

Conservation and research

I make very small quantities of orchil (maybe using 20 gr raw material) for research purposes and share my knowledge with those who are working on conserving precious artefacts such as the Vienna Genesis, a project in which I was involved a few years ago. These projects do not normally need large quantities of dyestuff. I have been given collections of UK dye lichens gathered in times when the activity was not as controversial as it is today. So I am in the fortunate position of having raw material to hand, which I occasionally share with researchers and conservators.

I never use orchil (or any lichens) for my studio work.

A paper on the Angola / Portugal sections of this blog was delivered in 2010 at the DHA 29 Conference in Lisbon.

Links:

Leyden and Stockholm Papyri The English translation used by the re-creation group

Download recent conservation research on the Vienna Genesis here